Be a Land Steward.

Sign up for Greenhouse Gases -

a weekly-ish newsletter that will teach you the science behind regenerative gardening, with action steps to help you make a difference in your backyard.

Sign up for Greenhouse Gases -

a weekly-ish newsletter that will teach you the science behind regenerative gardening, with action steps to help you make a difference in your backyard.

Have you ever had a deja vu moment at the compost pile? Like maybe, just maybe, an ancient version of you, somewhere, was recycling those kitchen scraps into garden nutrients thousands of years ago?

Well, turns out, our agrarian ancestors have been practicing regenerative agricultural techniques (like composting) through the millennia.

Regenerative agriculture is not just a trend—it's humanity's heritage, a reminder of our enduring relationship with the land.

The solution to climate change we strive for is not a distant dream but has been present with us for hundreds - sometimes thousands - of years.

Dive into this detailed timeline of sustainable agricultural practices to explore the history that inspires us forward as we address our current climate crisis.

We’ll explore the history of regenerative techniques like:

See this as a treasure trove of insight for the land steward, eco-conscious gardener, and environmental activist.

As we embark on this journey through time, let's not merely study the past. Instead, let's step into a shared mission to heal our planet.

Together, we can propel the solution of regenerative agriculture into the future — starting in our own backyards.

As we rewind the clock, we uncover soil health innovations that would impress even the most modern eco-advocate. Let's explore how our ancestors cultivated a relationship with the earth that was as nurturing as it was ingenious.

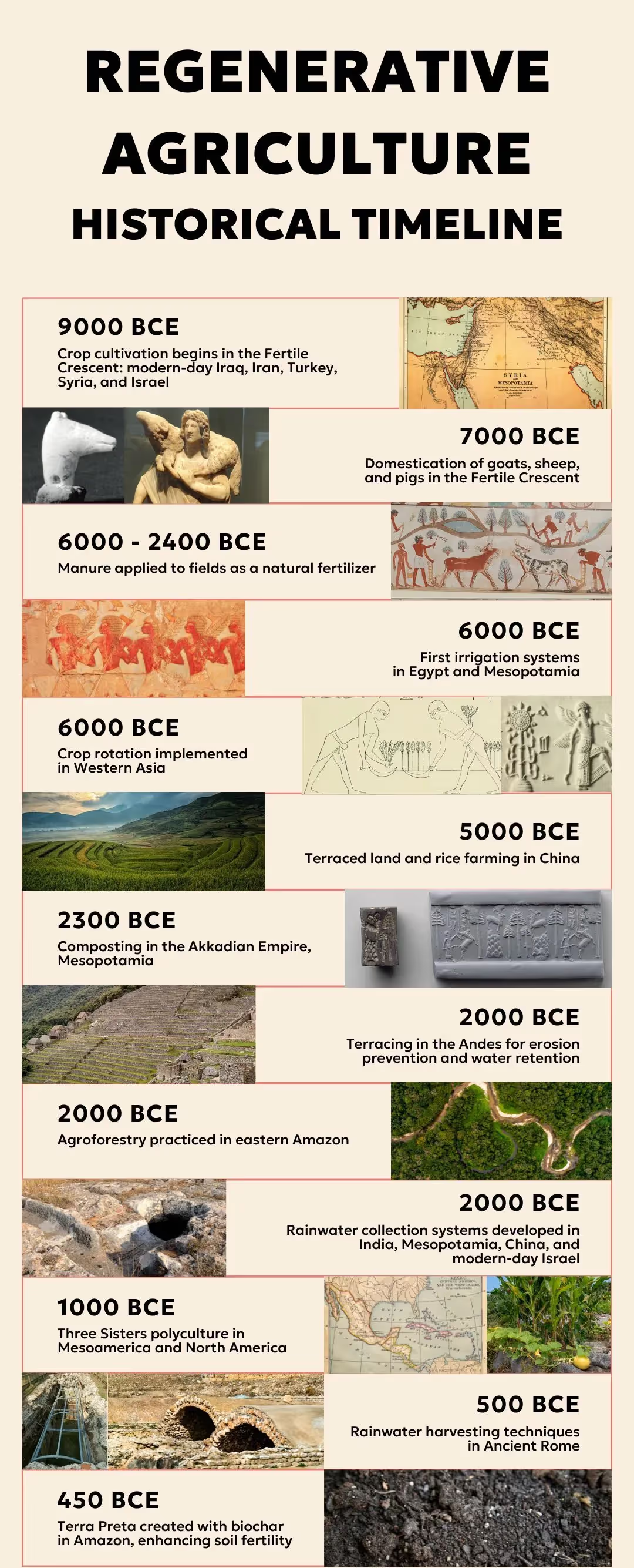

Imagine the legacy of that first seed planted in the Fertile Crescent, 11,000 years ago (History).

To say the least, it was a momentous occasion. Instead of traveling vast ranges of land as hunter-gatherers, we could now call one place home as we began to rely on a settled location for our resource needs.

As time went on, land stewards in the Fertile Crescent started to tend to wild sheep (Wikipedia).

Eventually, around 8000-7000 BCE, these stewards turned into shepherds, tending to domesticated goats, sheep, and pigs (Science, Nature)

It was around this time that agriculture continued to spring up and develop around the globe - either independently or learning from neighboring regions (Britannica).

Around 6000 BCE, farmers in Europe began to see the benefits of manure - from the relatively recently domesticated livestock - as an application for crop fertility (UNL).

We can see our ancestors learning, adapting, and developing throughout time as they continued to understand how to live in a symbiotic relationship with nature.

Simultaneously, in 6000 BCE, the earliest known irrigation systems were developed in Egypt and Mesopotamia (Wikipedia). Crop rotation emerged in Western Asia, which minimized soil depletion (Bioneers).

These modern-day sustainable solutions - composted manure, irrigation, and crop rotation - showcase how farmers were also looking for answers to adapt crops to their specific regions and resources.

This was especially important in a time without access to fertilizers and extensive plumbing like how we have today.

Our forebears were already engineering solutions to work in harmony with their environment.

We can see further developments in adaptability throughout time across the globe:

It’s a fascinating and beautiful thing, to see humans exploring techniques that today are synonymous with regenerative practices - thousands of years ago.

While the technology of the 21st century is certainly impressive - look at what the ancient world was able to accomplish with a very different set of resources and materials!

And today, their methods are the necessary actions that we take as sustainable farmers and gardeners in order to build soil health, tread lightly on the land, and sequester carbon.

Zoom forward to a time of empires and innovations. We’ll see the farmers of the past solving problems with many methods that have stood the test of time.

Cisterns of a Civilization (500BCE):

The ancient Romans were thinking ahead of their time as they started to build cisterns and other rain water harvesting systems to support their farms (UCSB).

.avif)

Amazon’s Ancient Fertility (450 BCE):

While biochar is a material that is getting a lot of attention now, it’s not a new innovation. In (at least) 450 BCE, we see the creation of Terra Preta, a climate-smart mavel in the Amazon

This is a soil enhanced with biochar and animal bones to boost the nutrition and the water retention capacity of the soil (Mongabay).

What’s especially mind-blowing about Terra Preta? The nutrients from the soil stewardship of the Amazon farmers is still present in the soil today (PubMed, Royal Society Publishing).

High-Altitude Harvests (300 BCE):

In the mountainous areas now known as Bolivia and Peru, crop diversity becomes important during times of drought and flooding.

We also see raised fields, called waru waru, utilized for crop success in the same situations (OAS).

Roman’s Bread and Circus Crop Carousels (200 CE):

Pasture rotation and crop rotation is practiced in the Roman Empire. This kept the land productive, the soil healthy, and their livestock well-fed. Both practices are relevant today in regenerative gardens and farms (Oregon State).

China’s Aquatic Two-for-one (300 CE):

In China, natural weed and pest control is practiced with a paddy rice-fish culture.

This ingenious method relied on the natural habits of the fish to eat pests and control weeds, all along the successful crop of rice. Fish also provided built-in fertilizer for the rice.

Then, the fish became a second harvest. Sustainable, productive, and pretty darn clever (IDRC).

Sri Lanka’s Edible Jungles (500 CE):

Forest farming emerges in areas of Asia, such as Sri Lanka.During this time, under King Vijaya, communities gathered together to plant trees, and homes were surrounded with a lush edible forest.

What’s interesting about this is that to this day in Sri Lanka, home gardens still grow a great deal of food in a forest landscape (Commonwealth iLibrary).

As we travel through this millennia, we see a series of techniques from around the world that contributed to water conservation efforts of the past.

Around 0 BCE in Northeast Africa, extensive irrigation and rainwater catchment systems are developed by the Kushite people in modern-day Sudan.

They utilized the rhythms of the Nile and the seasonal weather to provide necessary water for their crops year-round (Wikipedia).

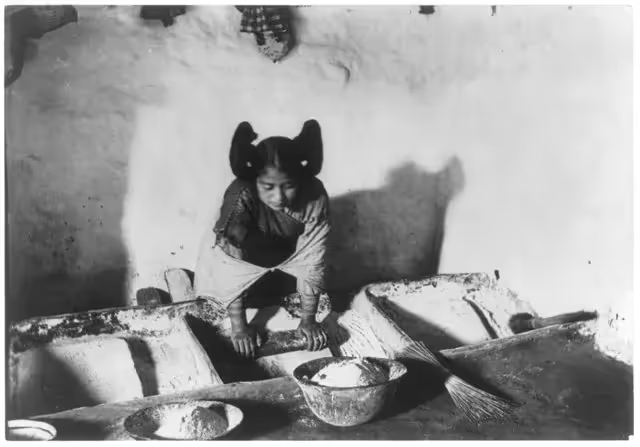

During the same time period in the Americas, the Hopi Nation totally flipped the script on farming. No water? No problem. Instead, they invented dry farming methods that rely just on rainfall.

In a place that gets around 10-12 inches of rain annually, this is no small feat.

Some of the dry farming techniques that were practiced 2,000 years ago are still continued by Hopi farmers today, such as:

Around 600 CE in the Americas, the Hohokam tribe implements irrigation systems to water their crops in present-day Arizona. The Hohokam continued to build and develop their irrigation system, with intricate canal systems that spread throughout the region (Britannica).

They also covered their soil in a stone mulch, in order to prevent evaporation (BYU).

In the arid climate of the region, the Hohokam created a farming system that understood the preciousness of water.

In 1000 CE, the Subak irrigation system was developed in Bali, Indonesia.

This is a complex system that involves forests, rice paddies, terraces, canals, and temples.

Around a thousand years later, this innovative way of farming was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site (Wikipedia).

Around 1200 CE (estimated), the Sahel region of Africa developed the zai pit planting technique. This is a system of water and organic matter collection.

One small pit is dug for each plant. These pits are like bowls that can catch rainwater, and can sustain the crops even during times of scant rainfall.

Part of the reason that this works is because the depth allows the plant to access water that is lower in the soil layers.

The other reason is because manure and compost are added to the pits, which act as a mulch to prevent evaporation.

As an added benefit, the compost delivers necessary nutrients to the crops (GCA).

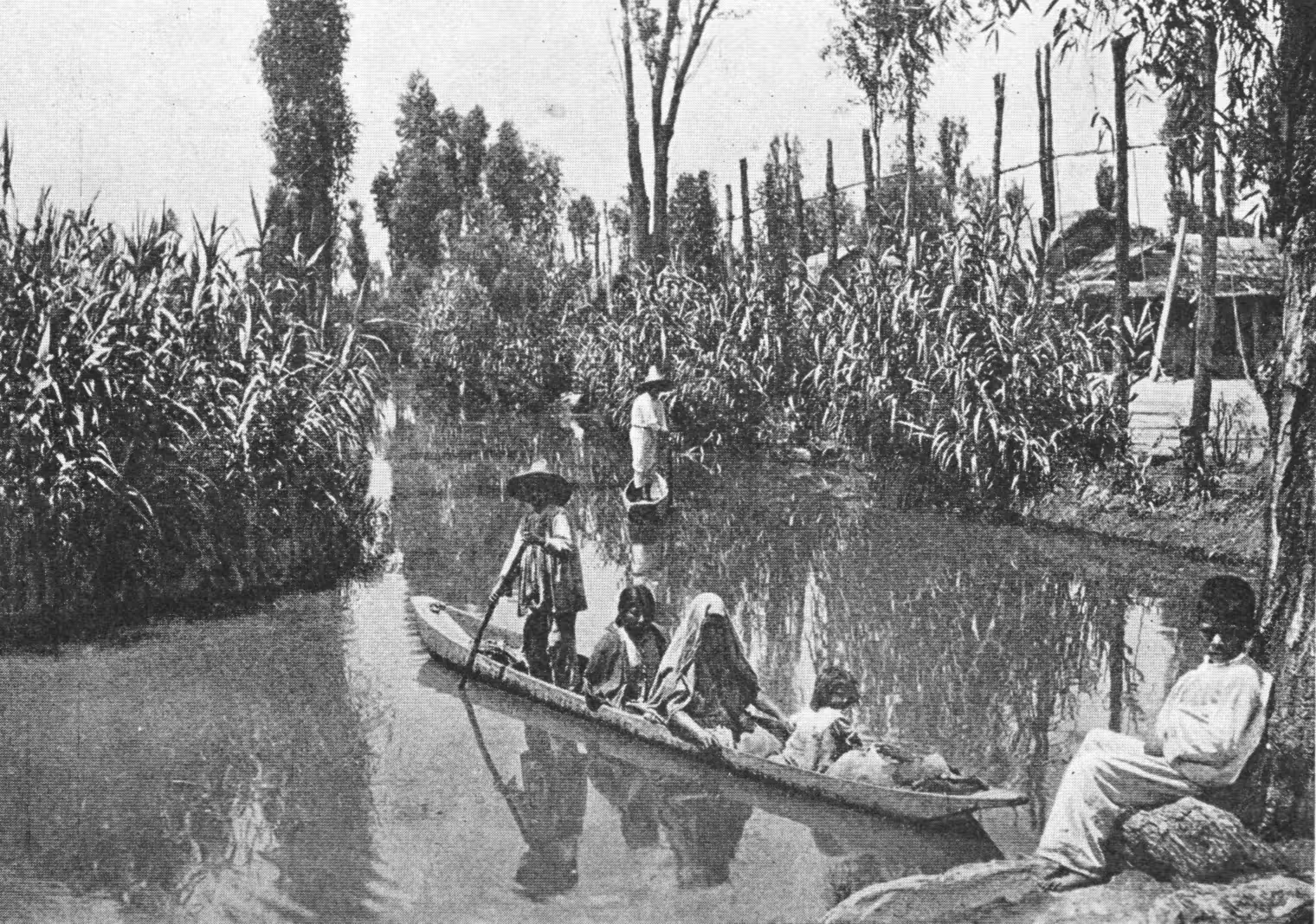

Back in the Americas, the time period between the 1200s-1500s saw the development of chinampas. This invention of Aztec ingenuity is a system that utilized the reliable water source of lakes to build up floating gardens in shallow zones.

The method of creating these gardens is fascinating:

(UH Hilo)

Fast forward to the chapters of modern regenerative agriculture, where the plot thickens and the stakes get higher. Here's where agricultural biodiversity becomes the hero of our story in the fight against erosion and soil degradation.

High-level resiliency

1500 CE: Resilient crops developed by the Incas for the harsh conditions of the Andes (Smithsonian).

Zooming in:

1660 CE: Thanks to the invention of the microscope, scientists are now able to see soil microbes.

This miniature soil universe is the key to plant health, and is the foundation upon which our food system is built (Royal Society).

Rotation Implementation:

1800 CE: Four year crop rotation system practiced in Europe which increases yield and supports livestock (Ag Proud).

Water delivery in the forest

1800 CE: Bamboo drip irrigation waters the agroforestry systems of Khasi and Jaintia Hills region in northeast India (Asian Agri History).

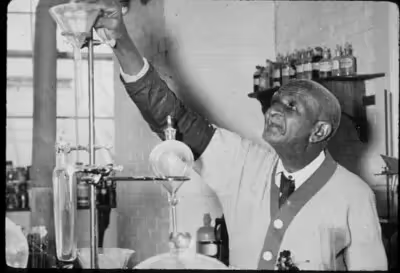

A revolutionary

1900s: George Washington Carver, the father of regenerative farming in the modern age, placed an emphasis on crop rotation and organic methods.

Known for inventing dozens of ways to turn the humble peanut into possibility, his legacy in soil health resonates to this day.

Carver’s regenerative wisdom helps today's farmers think beyond the cash crop, nurturing a more diverse, resilient, and harmonious ecosystem (Live Science).

Out of the dust

1930s: The Dust Bowl prompted the emergence of the no-till farming movement. From this environmental disaster, soil conservation became a more thoroughly researched science (PBS).

There's always more to learn

1940s: The soil stewardship innovations of farmers from India and Barbados is shared with the English-speaking world by Sir Albert Howard. This further propelled the sustainable agriculture movement (Global Earth Repair).

In the 70s and 90s, Organic farming principles gain prominence, with an emphasis on soil health. This was due to the sustainable change-makers and innovators of the last 60 years.

Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez

1960s: Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez create United Farmworkers to support farm labor rights and worker health. This included advocating for the banning of pesticides.

Dolores Huerta continues to advocate for farm workers and the land to this day (National Women's History Museum).

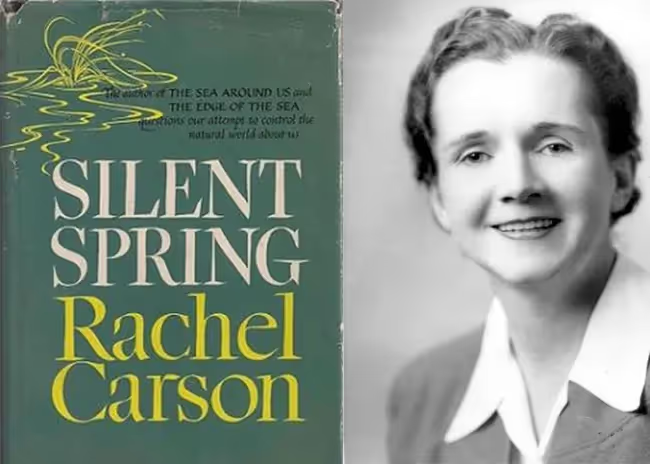

Rachel Carson

1960s: Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” didn’t just ruffle feathers; it launched an environmental crusade that reshaped how we view our impact on the natural world.

She wasn’t just an author: Carson was a clarion call for ecological stewardship.

Simcha Blass

1960s: The invention of drip irrigation emitters by Simcha Blass in Israel provided a smarter way to hydrate crops and conserve water (Jewish Telegraphic).

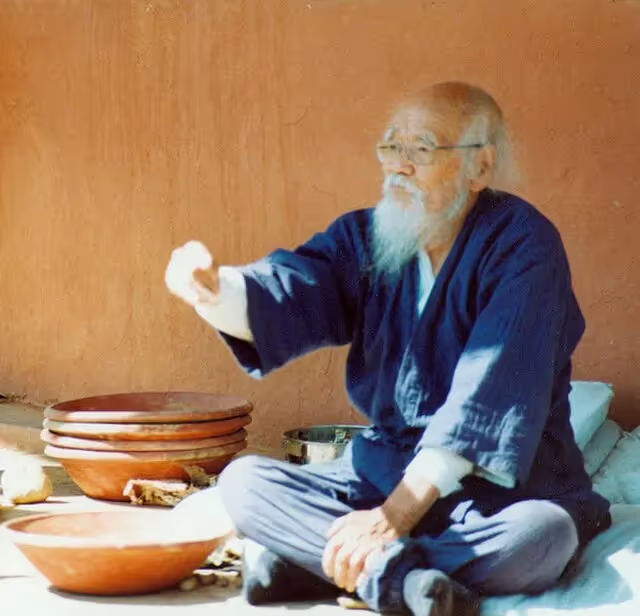

Masanobu Fukuoka

1975: Fukuoka’s "One Straw Revolution" became manifesto for the organic no-till and mulching movements.

While he coined the term “do-nothing farming” - the foundation of today’s “lazy gardening” - his methods of farming did a lot to inspire a revolution of the sustainable farming movement (One Straw Revolution).

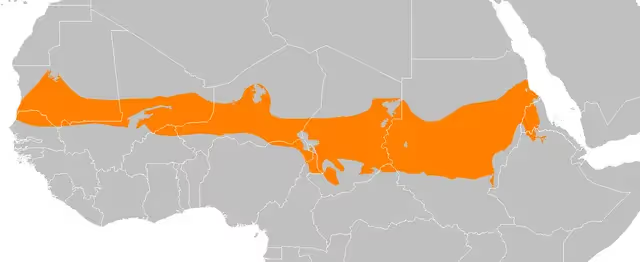

Yacouba Sawadogo

1980s: Sawadogo was a visionary of hope during an extensive drought in West Africa. He advocated for water collection and soil health principles, and re-introducted ancestral farming techniques. This helped farmers build resilience in a harsh climate and develop productive crops to feed their families (UNEP).

JADAM Method: Simple and Smart

In the 1990's, Youngsang Cho figured out accessible ways to grow food without hurting the environment. It's all about building soil health and using what nature gives us instead of harsh chemicals. What's empowering about this eco-friendly method is that it can be made by famers for a very low cost (JADAM).

Braiding Sweetgrass

One of the most pivotal books in environmental movement of the last decade is Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer. A citizen of the Potawatomi Nation and trained scientist, Kimmerer's book opened the doors to many for how to tend to the land during a climate emergency. While published in 2014, the book has become increasingly popular for new and long-time naturalists alike (Washington Post).

A Pivotal Paper from Rodale

In 2014, the Rodale Institute releases a white paper called "Regenerative Organic Agriculture and Climate Change." This paper explained how regenerative farming can help stop climate change. More people started to catchon to how farming can be part of the solution, not the problem.

Afro-Indigenous Regenerative Farms

Leah Penniman is the co-founder of Soul Fire Farm in New York, where she advocates for regenerative farming practices and supports Black and Brown farmers to tend to the land. Focused on ending racism and environmental harm in the food system, Soul Fire Farm offers training programs that focus on Afro-indigenous land stewardship methods to BIPOC farmers.

Penniman released her book Farming While Black in 2018, and Black Earth Wisdom in 2023, both of which focus on uplifting the voices and wisdom of Black farmers and environmentalists (soulfirefarm.org).

COP28: The World Gets Serious

Fast-forward to 2023 at COP28. For the first time, agriculture is a main topic of discussion. There was a call to change how we grow food to make a huge difference in the fight against global warming (The Guardian, Reuters).

Today: Regenerative Farming is a Hot Topic

Right now, the indigenous techniques that make up regenerative farming is the talk of the town. It's got everyone's attention because it's a powerful way to take care of our planet. It's not some passing trend—it's a real, solid way to help heal the earth while we grow our food.

We stand upon the soil of our agricultural ancestors, who were constantly adapting to the land, problem solving for resilience, and discovering ways to survive in sometimes seemingly impossible conditions.

As we speculate on the future of sustainable gardening and agriculture, we have a history book of age-old methods to draw upon. This ancient technology can go forward to inspire new growth for regenerative agriculture that isn’t just sustainable, but thriving, active, and alive.

So, let's roll up our sleeves and get our hands dirty with purpose and passion. With every seed we sow, we're penning a love letter to future generations—a message that says, "Hey, we cared, we loved, and we grew a resilient world blooming with life.”

This chapter in regenerative farming history is still unwritten, and it's ours to author with every sustainable choice we make.