Be a Land Steward.

Sign up for Greenhouse Gases -

a weekly-ish newsletter that will teach you the science behind regenerative gardening, with action steps to help you make a difference in your backyard.

Sign up for Greenhouse Gases -

a weekly-ish newsletter that will teach you the science behind regenerative gardening, with action steps to help you make a difference in your backyard.

1. Elderberry Species Overview

2. Key Identification Features

3. Ecological Significance of Elderberries in the PNW

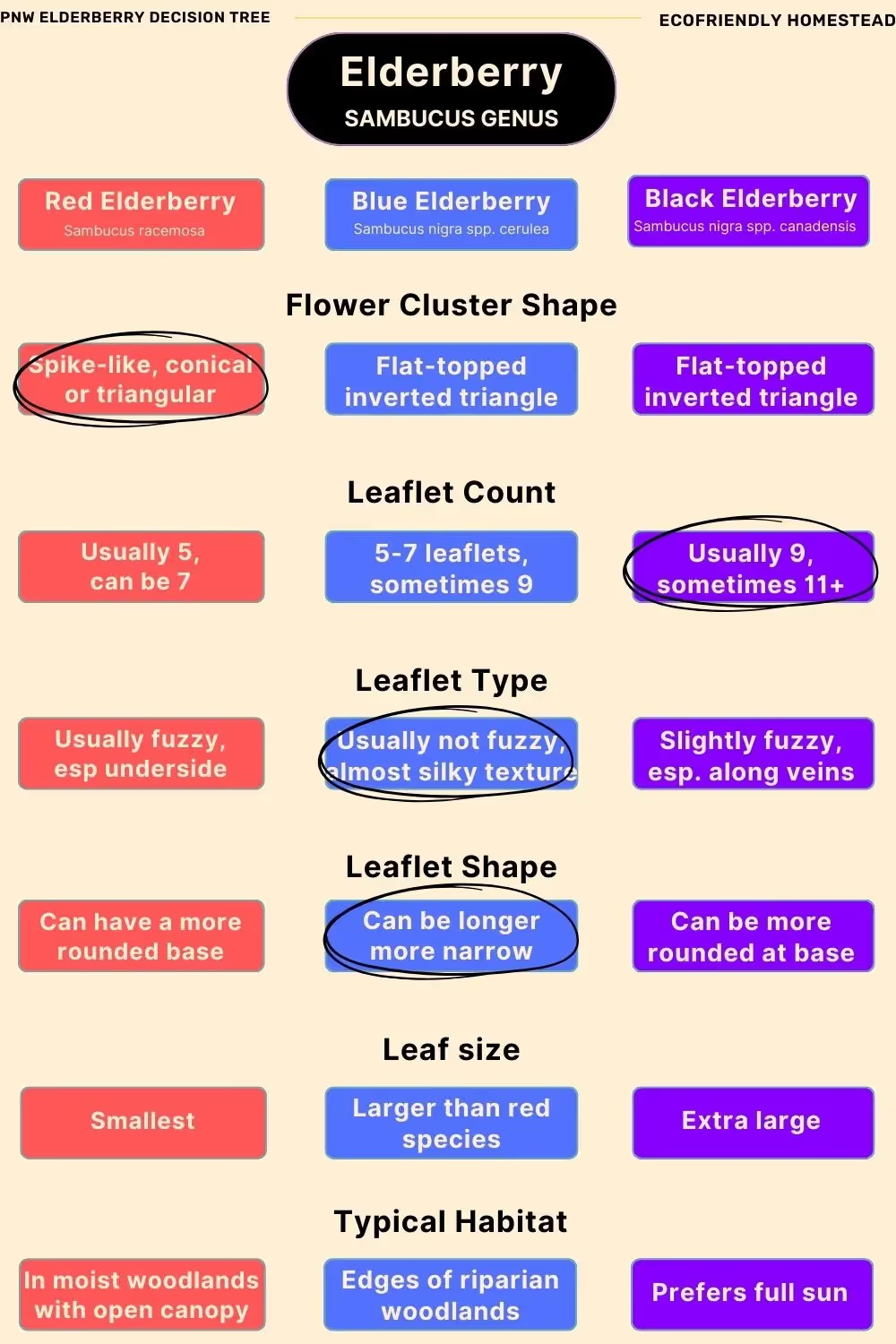

Elderberries fall into three basic categories: red, blue, and black.

It's fairly straightforward to distinguish them when they are fruiting based on the color of the berries. But for most of the year, elderberries won't have branches heavy with their colorful fruit. If you want to identify what kind of elderberry you're looking at, this guide will help you understand the key features to confidently identify your elderberry species.

I’m fortunate enough to have all three of these elderberry species in my yard, each planted by birds or other wildlife. The blue elderberries were the first to catch my eye, growing resiliently from old stumps at the edge of wooded areas. Red elderberries revealed themselves in the small forested part of my yard, tucked beneath the canopy. The black elderberry, thanks to some critter visitors, found a home in my greenhouse—twice!

As a plant enthusiast and home herbalist, I initially struggled to notice the subtle differences between these species. For me, it's easy to recognize an elderberry bush or tree, but to go a step further and id the specific type can be challenging.

This knowledge is vital for foragers and herbalists; black elderberries are considered the safest for medicinal use (when cooked correctly), while red elderberries remain toxic regardless of preparation. Proper identification also helps avoid toxic look-alikes, such as the purple berries of pokeweed or the white flowers of the deadly water hemlock.

Driven by curiosity and a bit of stubbornness, I indulged my inner botanist. I scoured numerous sources and conducted some backyard field study in order to compile a meticulous identification spreadsheet

Now, the once-confusing array of leaves and clustered blooms has been distilled into a few significant features for each elderberry type. In this visual guide, I share my elderberry ID chart with you, along with essential insights and images. By the end of this guide, you’ll become a skilled elderberry identifier, ready to recognize and differentiate these fascinating plants with ease.

Red Elder (Sambucus racemosa)

Blue Elder (Sambucus nigra subspecies cerulea)

American Black Elder, Common Elder (Sambucus nigra subspecies canadensis)

(USDA FS, USDA, WVU, WIkipedia, Sparrowhawk Native Pants, Crows Path, Three Rivers Parks, USDA FS, Portland Nursery, Oregon State University, Strictly Medicinal)

(USDA FS, Britannica, USDA Plants Database, WNPS, WSU ,Texas Wildbuds)

Here is a more in-depth sortable + interactive chart to more clearly see the different characteristics of the elderberry species commonly found in the Pacific Northwest.

Scroll through to see the main distinctions, including characteristics of leaves, stems, blooms, height, habitat, and location. You'll also see my citations towards the right.

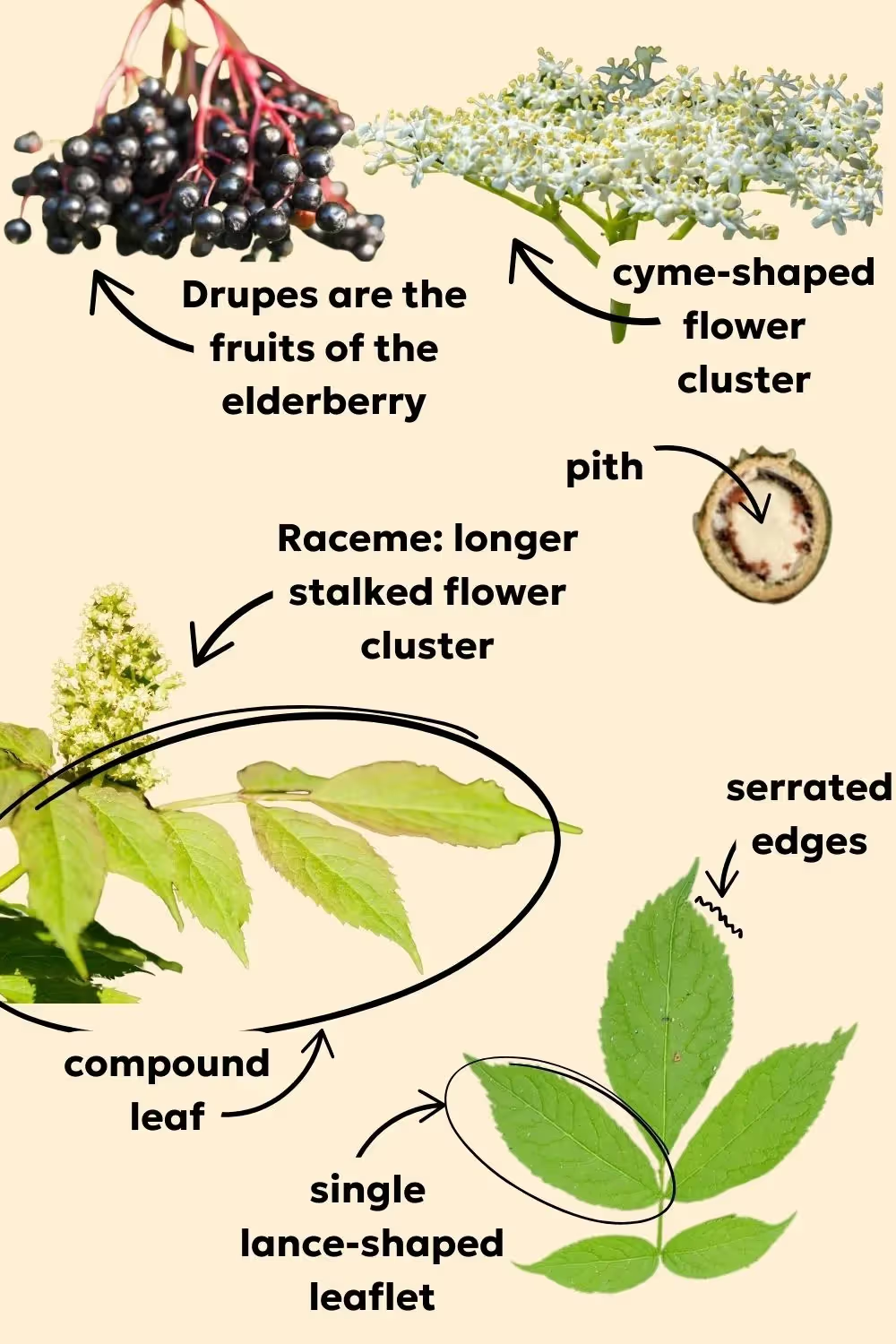

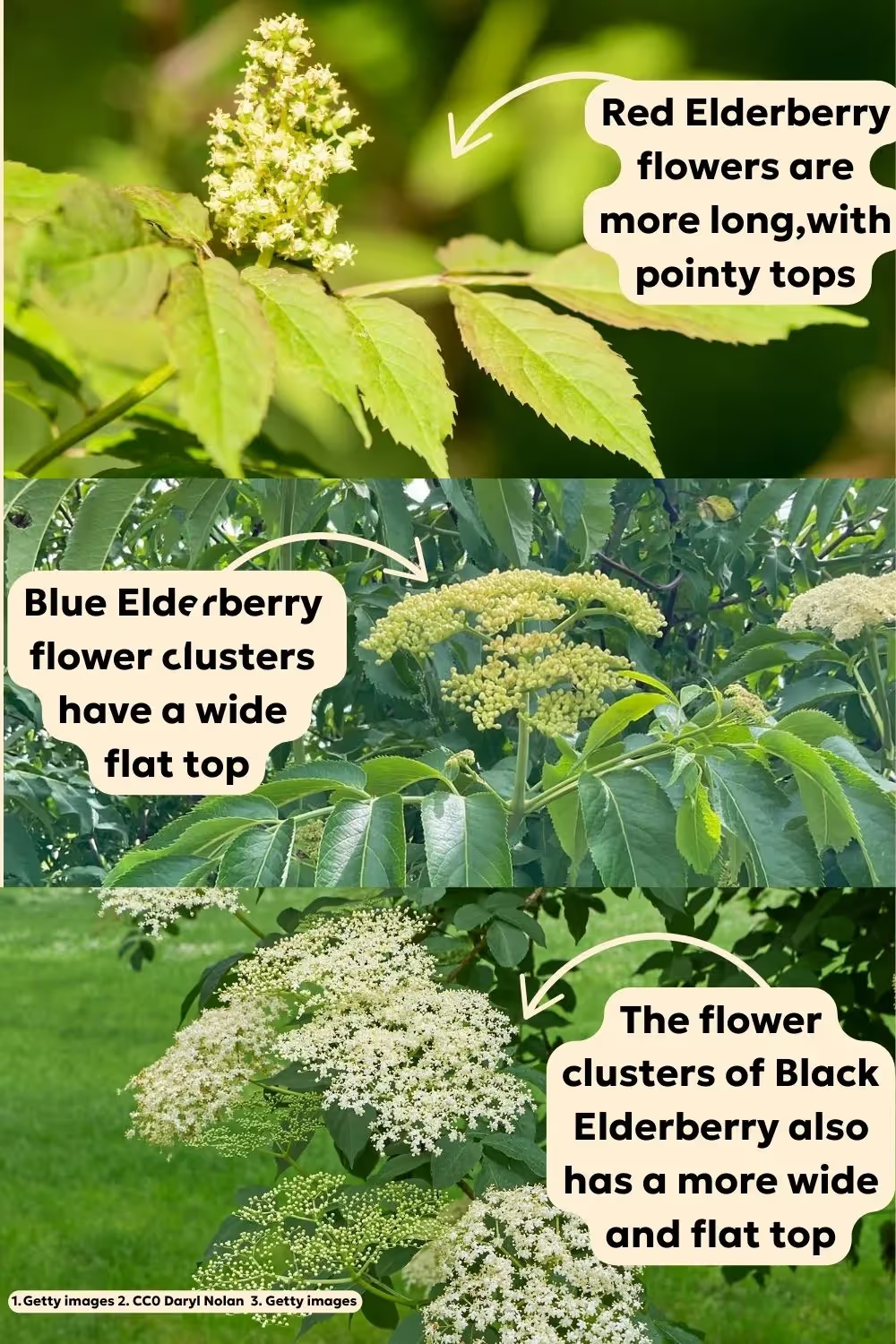

One of the key features to remember with elderberry species that are native to the Pacific Northwest is the meaning of racemosa - the species name of the Red Elderberry. This word points to the "raceme" or spike-like structure of the flower cluster that occurs in Red Elderberry. It kind of resembles an ice cream cone or diamond shape.

Both Blue and Black Elderberry have more of an inverted triangle shape with a wide flat top that will curve open like an umbrella. The flat top of the blooms are a distinguishing feature.

Both of these characteristics in cluster shape carry through to the berries, which is a helpful feature when identifying unripe berries.

In general:

In looking at the leaves in an image from the US Forest Service, it was clear that Red Elderberry has a smaller leaflet and leaf size when compared to Blue Elderberry. I cut off a branch with a similar growth stage off of both species to see this difference for myself.

I then cut off a branch from my bird-gifted Black Elderberry. My specimen didn't have any hardened bark like my Blue and Red species, but that almost makes the size difference even more interesting. The Black branch was coming off of a main stem similarly to the other two.

It's important to note that the Black Elderberry is in a greenhouse. While it did die back quite a bit over the winter, it's in a spot with full sun and gets watered regularly. This can account for some of the size difference here.

Other indicators can be seen if you look very close to the leaflets: Blue elderberry usually has smooth leaflets - they almost feel silky or synthetic to me.

Red elderberry has leaves that are fuzzy - they almost feel like a hazelnut leaf in terms of their softness. Black elderberry leaves are fuzzy as well, but slightly less so.

In general:

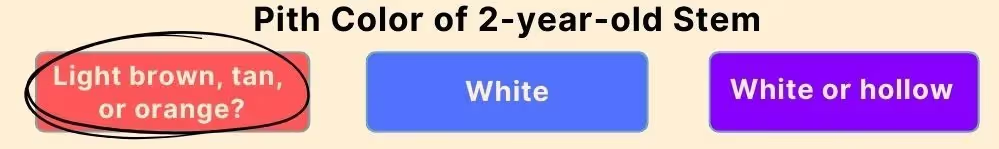

The pith is the center part of the elder tree branches. When present, its color can be an indicator of the species. Look at the pith on second-year growth.

%20red%20elder%20pith.avif)

In general:

I saved the easiest for last! When the berries are ripe, their color is a clear give away for which Elder species you're looking at.

Note that there is a white powdery coating on the blue elderberries that can be wiped off to reveal a deep navy berry that could be interpreted as black. However, that powdery coating is only present on the blue species.

Important traits of elderberries:

Key ways elderberries help nature:

Historical Context:

In conclusion, the native elderberries of the Pacific Northwest are not just a feast for the birds and humans (when properly prepared, remember!), but also vital players in our ecosystem.

When you learn to identify these resilient plants with the tools provided in this guide, you can be an active participant in ecological conservation.

Do elderberries need another tree for fruit producction?

According to Richo Cech, renown herbalist and owner of Strictly Medicinal Seeds, open-pollinated wild elderberries do not need to cross-pollinate. While theyare self-fertile, he advises that you will get more fruit set if you plant two or three.

Can you eat the flowers of red elderberry?

Richo Cech advises against this. He says, "Red elderberry is high in cyanogenic glycosides," which are toxic. It should be noted that all parts of the elderberry plant, including blue and black elderberries, contain cyanogenic glycosides. The berries and flowers can be toxic if not properly prepared.

Can different species of elder (i.e. red and blue) cross-pollinate?

Cech states that it's unlikely that Red Elderberry will cross with Blue or Black Elderberry. He explains, "differences in the timing of blossoming with the different species generally accounts for a lack of hybridization."

Is Elder the same as Box Elder?

No. Elder is in the sambucus genus, and box elder is in the acer (maple) genus. Box elder is invasive in some counties of Michigan and Wisconsin, and is not native to Washington, Oregon, Idaho, or western Montana. It is found in some parts of California (USDA FS).

Should I trust a random stranger on the internet to tell me how to eat and process elderberries?

Nope. Consult a well-trained herbalist and naturalist in your area who can teach you the proper way to identify and prepare elderberries safely.

Additional Resorces:

USDA

WVU

*Disclaimer: While I strive for accuracy, I'm human and so there may be errors. This blog is for educational purposes only and you assume any and all risk associated with plant ID, foraging, and consuming plants. I'm not a professional, so don't take any information as professional advice. You understand that any errors can cause serious illness or death. Before working with a plant in anyway, consult a local guide who understands both ID and proper preparation. Be smart, friend!