Be a Land Steward.

Sign up for Greenhouse Gases -

a weekly-ish newsletter that will teach you the science behind regenerative gardening, with action steps to help you make a difference in your backyard.

Sign up for Greenhouse Gases -

a weekly-ish newsletter that will teach you the science behind regenerative gardening, with action steps to help you make a difference in your backyard.

Obscuring the busy street from view, my naturally occurring hedgerow is noisy with a hum of its own.

No, not the hum of passing cars.

This is the noise of bees and wasps at work, dancing from flower to flower. A hummingbird zips by, searching for nectar to drink. The yellow and black swallowtail butterflies dance from blackberry flower to flower.

The hedgerow's activity replaces the main road's hustle and bustle. While the meadow next to this hedge is dotted with wildflowers that bring in the bees and other beneficial insects, the hedgerow is where they really congregate in droves.

Hedgerows give these insects a home, which is key to growing flowers and fruit on my homestead.

A study featured in the Journal of Applied Ecology brings this fact to life, with findings that densely planted hedgerows can amplify pollination and subsequent fruit and seed production by up to 70%!

While bees are tiny, their role is massive in terms of food production. I have them to thank for the berries that I forage, for the apples and pears that grow in the orchard, and many other things that I enjoy eating from my homestead.

Research from California's Central Valley proves that hedgerows have higher numbers of native bees in comparison to just leaving field borders untended. This study found a remarkable 7x increase in the number of rare native bee species on hedgerow flowers over those found on untended pasture borders.

Hedgerows have the opportunity to provide something essential to these beneficial insects: early sources of food.

Research on Science Daily shows that adding early-blooming plants to hedgerows can boost bee colony survival from 35% to an amazing 100%.

Let's discover how the bustling life in hedgerows supports pollinators - like a multi-level pollinator patch on a grander scale.

Through the lens of each season, I've witnessed the transformation of my hedgerow from a skeletal winter refuge to a springtime haven of hope, buzzing with the first bees. My observations echo the cyclical support systems the studies advocate for- beneficial insects find early blooming trees and plants as a vital food source.

For bees, spring is pivotal. In my naturally-occuring hedgerow, early bloomers like pussy willow, hazel, and maple provides the year's initial nectar, delighting the emerging bees and closing the 'hungry gap.’ Serviceberries and Oso plums also bloom with soft white flowers during spring.

Just as purple broccoli and winter kale feed us during the "hunger gap" when little else grows, hedgerows give bees early nutrition before our gardens bloom.

Each year, as the frost retreats and the days stretch longer, my anticipation grows with the budding plants. This year, I remember the sunny morning when I saw my first bumblebee of the season, visiting a fresh dandelion on the edge of the hedgerow. This delightful fuzzy friend signaled that the hedgerow was once again ablaze with life.

Dr. Tonya Lander of the University of Oxford shares the hedgerow plants that excel at supporting pollinators. She mentions the presence of early nectar providers, such as “red dead-nettle, maple, cherry, hawthorn, and willow, […] improved colony success rate from 35% to 100%.”

Dr. Lander co-authored a study released in March 2024, providing these findings.

The study showed that bumblebee food requirements peak from March to April, a critical period when other plants have yet to bloom and offer sustenance. Most pollinator patches, for example, are often not blooming until May or June.

Bees face a critical challenge that the study uncovers: if they can't find enough nectar for just two weeks, it's not only their daily food that's at risk. The future of the bee colony, including the birth of new queens, could drop drastically - by up to 84%.

This study highlights how hedgerows provide a critical resource for bees emerge in the early spring - a warm welcome to the near year with pussy willows and hazel catkins.

Other studies have mentioned blackthorn, hawthorn, rose, and bramble species to provide early sources of food for the bees.

UCANR also notes manzanita and wild lilac as early nectar blooms, if they are native to your region.

As summer crops bloom, pollinators drawn out from the shelter of hedgerows into the fields to help fruit and seed set, improving yields, according to OSU.

Gardener’s World suggests hedgerow trees like linden, black locust, and elderberry to offer nectar and pollen in the summer months.

Herbaceous hedgerow favorites listed by UCANR for summer blooms include salvia, yarrow, native artemisia species, buckwheat, ocean spray and penstemon.

In my own natural hedgerow, roses and blackberries bloom on the south side. On a sunny day in the summer, bumblebees and swallowtail butterflies are always zipping about. As I forage, I often have a soundtrack of bees and hummingbirds whirring in the background.

Autumn brings its share of late bloomers, keeping the hedgerow humming until the first frosts come.

Xerces Society offers plants to grow for pollinator food sources in the fall such as echinacea, rudbeckia, native asters, and native salvia species.

We have some native goldenrod at the edge of our woodland that provides a lush display of yellow flowers that are always heavy with pollinators in September and early October.

While winter’s quiet offers something vital for pollinators - a place to overwinter, safe from the elements and predators.

Layers of leaves, twigs, and stems form safe places for nesting and overwintering, protecting pollinators.

Oak trees and Black Cherries provide overwintering shelter for butterflies.

For bees and beneficial insects to overwinter effectively, it's advised to leave shrubs like elderberry, raspberry, and sumac unpruned during winter, as their stems offer crucial shelter (OSU, MSU). Carpenter bees are one example of a beneficial insect that lives in hollow stems - like those of the blackberry.

Maryland DNR recommends herbaceous plants with great stems for overwintering insects. These include Swamp milkweed, Joe Pye weed, coneflowers, wild bergamot, and goldenrod.

They also say that dead trees or logs give a warm winter home for bees and a shelter for butterflies and moths.

Have you heard of the initiative from the Xerces Society to “leave the leaves” for pollinators? Fallen leaves in a hedgerow can contribute to this movement. They mention that most butterflies and moths need leaf litter to provide winter housing for eggs, caterpillars, and adults. The queen from certain bee species will also spend her winter in leaf litter.

The structure of hedgerows - long and linear - becomes especially beneficial to pollinators when it connects two otherwise separate habitats.

Think of hedgerows as highways that connect different habitats. New research from an analysis published in 2024 shows that these green highways are crucial for keeping pollinator numbers healthy, as they can travel and find new areas to live and gather food.

They note that hedgerows can be traveled for migration by pollinators and offer a connection between food sources and mating locations. The also study found that hedgerows linked to forests especially help butterflies.

Don’t worry if your hedgerow doesn’t connect with woods, though. Pollinators were found to have high population in hedgerows that were in “simplified landscapes, suggesting that these structures serve as a "last refuge.”

This quote from Scott Black, Executive Director of the Xerces Society, highlights the urgency of connecting habitats with hedgerows:

“...if we maximize field edge plantings with diverse native plants and minimize pesticide use, we can both improve pollinator survival and protect our future crops and food supply.” - Xerces Society

In our time of climate change, hedgerows offer protection from extreme weather. For example, Ilona Naujokaitis-Lewis, while studying various agricultural settings for research in Canada, found that hedgerows could have temperatures up to 15 degrees less than in the nearby fields. That means on a 90 degree day, pollinators in the shade of the hedgerow could find zones that were around 75 degrees - a big difference!

A study out of Germany notes found this temperature difference in hedgerows to be especially important for wild bees. The cooler temperatures of habitats like hedgerows increased the biodiversity levels of these benefical insects.

Xerces Society mentions that the corridor effect of hedgerows can help beneficial insects to travel over distances to find reprieve from harsh weather.

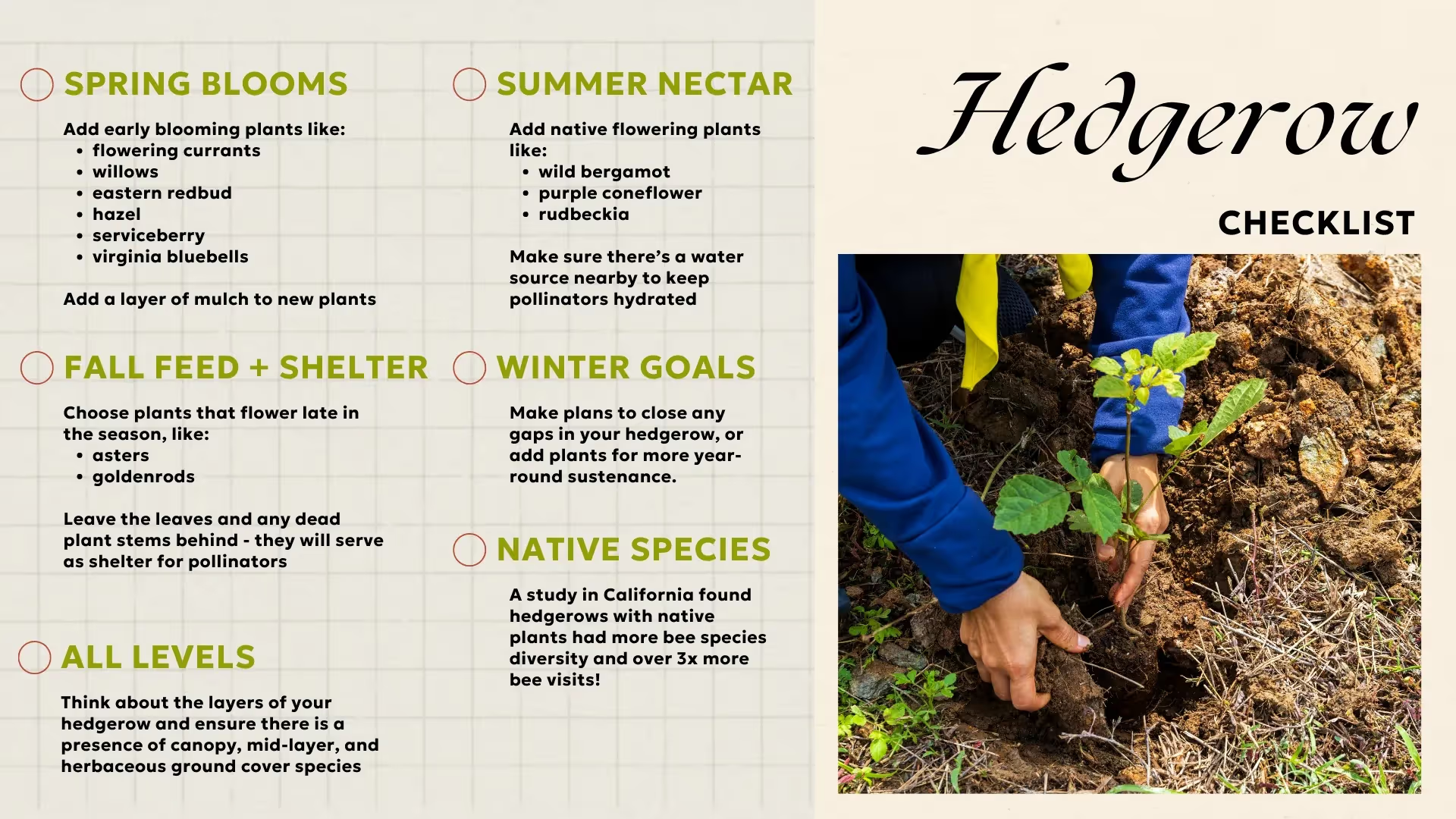

Creating a pollinator-friendly hedgerow means ensuring there's a steady supply of food throughout the year. Each season should bring a new wave of blooms to support a diverse range of foraging insects. Let's break it down by what to plant for continuous sustenance:

Spring:

Summer:

Autumn:

Winter:

(sources: UGA, Oregon State, Xerces 1, Xerces 2, Xerces 3, PHEG, pollinator.org)

Native plants fit well with the local weather and soil and work perfectly with local pollinators. Bees evolved with these botanical comrades, forming a time-tested partnership.

These native plants make your garden strong and right for your area.

A study in California found that native plant hedgerows hosted significantly more native bee species (16 species) compared to non-native hedgerows (9 species).

Building your hedgerow with layers, from ground plants to tree tops, makes a diverse habitat.

A meta-analysis found the importance of structural diversity and layering of hedgerows to correlate with pollinator population.

For example, a study in the UK from 2017 shows that “Considering the foraging of pollinators on hedgerows, hoverflies were found visiting understorey flowers significantly more than flowers on plants within the hedgerow”

This vertical diversity mirrors a natural forest to offer homes for the nesting bees and shelter-seeking butterflies.

Spring:

Summer:

Autumn:

Winter:

Hedgerows, often brimming with blossoms, serve as critical lifelines for pollinators in agricultural landscapes. They sustain a variety of flowering plants, providing a year-round buffet for bees and other insects. This continuous food source is vital as it helps maintain pollinator populations, ensuring that they are available to fertilize crops when needed.

In fact, as the University of Chico points out, "The annual value of crops pollinated by wild,native bees and other pollinators in the U.S. is estimated at $3 billion."

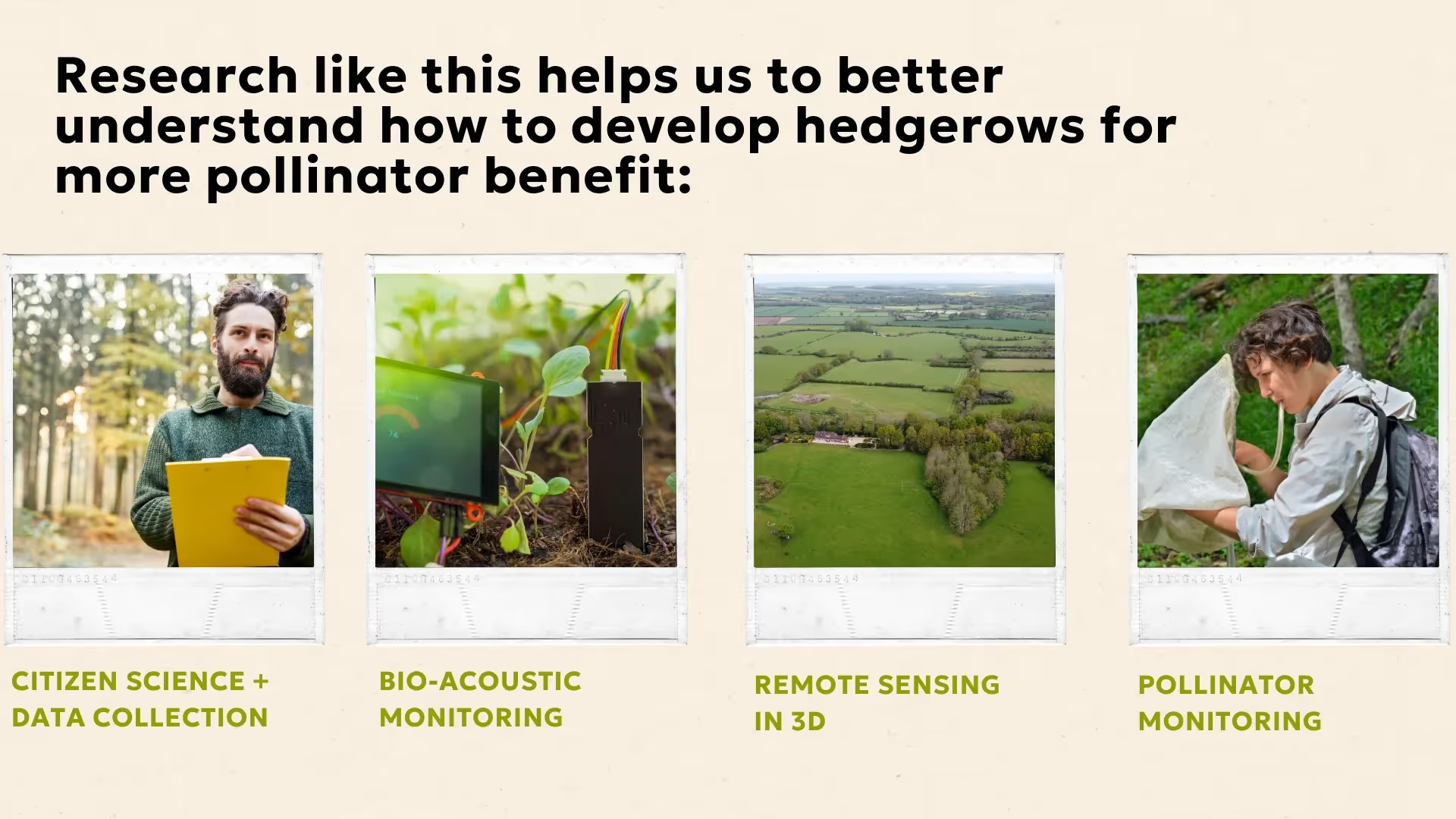

Citizen science projects can help us better understand how to improve hedgerows for beneficial insects.

Through initiatives like the Surrey Wildlife Trust's Hedgerow Heroes project, naturalists survey hedgerows across the UK. These volunteers gather valuable data on hedgerow health, plant diversity, and buzzing wildlife activity, painting a clearer picture of where our efforts to preserve these habitats stand.

Breakthroughs in bio-acoustic recording technology are like putting a stethoscope to the heart of these habitats, capturing an invisible yet captivating soundscape. These devices let us tune into frequencies of life – specifically for tracking bats within hedgerows.

Polly - a pun of a name if I've ever heard one - is a device from agrisound that farmers and conservationists can use to acoustically monitor pollination events.

These advances in bio-acoustic recording technology enable prolonged monitoring of wildlife in hedgerow habitats. The data can reveal how different hedgerow management practices influence biodiversity.

Imagine if we could soar above the land, our vision unimpeded by the bounds of human sight, able to perceive every hedge-rowed vein that crisscrosses through the landscape.

With modern marvels like hyperspectral imaging and LiDAR, we're close to doing just that.

These methods could help identify gaps or degraded sections requiring restoration, as well as map hedgerow networks to understand their role in facilitating wildlife movement.

Have you ever watched a bee in your garden, bouncing from flower to flower in a tireless quest for nectar?

To better choreograph our conservation efforts, scientists are now exploring technologies like AI and digital tracking devices, transforming bees into living datasets.

This morning, I walked the line of the hedgerow as I do every day, but with a special eye out for my beneficial insect friends. Fuzzy bumblebees, tiny bes, a variety of flies, and a few moths all moved throughout the landscape, traveling the corridor in search of flowers and resting places

In researching this article, I have a newfound appreciation for hedgerows as towering pollinator patches. They're lifelines for bees, butterflies, and countless other beneficial insects. Through their year-round blooms and shelter, they support the delicate balance of nature that our own food sources ultimately depend on.

So, as stewards of the land, let's cultivate and preserve these vital corridors. Whether it's choosing the right mix of plants or adopting sustainable practices, every action we take can reinforce this synergy between pollinators and plants.

In nurturing our hedgerows, we do more than just enhance our gardens—we bolster an entire ecosystem. With each tree or native flower planted, we're securing a better future for pollinators and for ourselves. It's a simple truth: the health of our hedgerows reflects the health of our planet, and every effort to sustain them is an investment in the continuity of life.