Be a Land Steward.

Sign up for Greenhouse Gases -

a weekly-ish newsletter that will teach you the science behind regenerative gardening, with action steps to help you make a difference in your backyard.

Sign up for Greenhouse Gases -

a weekly-ish newsletter that will teach you the science behind regenerative gardening, with action steps to help you make a difference in your backyard.

Keystone species are important because they significantly influence their habitat. Their behaviors create landscapes, and encourage plant, insect, and animal populations.

These vital organisms can create different ecosystems, such as the Great Plains. They also provide food and shelter, pollinate plants, and offer population control.

For example, beavers create dams that shape waterways. Wild cherry trees are a larval host plant to hundreds of caterpillars.

Regenerative agriculture and organic no-till gardening practices support keystone species in your backyard.

In this keystone species guide, you’ll learn:

Read on to learn why these species are integral to their habitats.

The concept of keystone species was developed by biologist Robert Paine based on his observations of sea stars in the Pacific Northwest.

His research in 1966 highlights how a single species can impact its ecosystem, even down to the temperature of the environment.

In 1969, he coined the term “keystone species” in a Letter to the Editor published by The American Naturalist.

“…the species composition and physical appearance were greatly modified by the activities of a single native species high in the food web. These individual populations are the keystone of the community’s structure, and the integrity of the community and its unaltered persistence through time, that is, stability, are determined by their activities and abundances.” - Robert Paine

So from this, we know that these criteria must be fulfilled:

There has been further research to expand on Paine's foundational work, and we now have a deeper understanding of these pivotal organisms.

The paper “Challenges in the Quest for Keystones” helps to further define Paine’s concept.

This paper clarifies that keystone species do not usually have high populations in their habitat. In contrast, they make an impact “much larger than would be predicted from their abundance.”

The services of keystone species include:

This concept is similar to ecosystem services. Ecosystem services are benefits that plants and animals give to their surrounding environment.

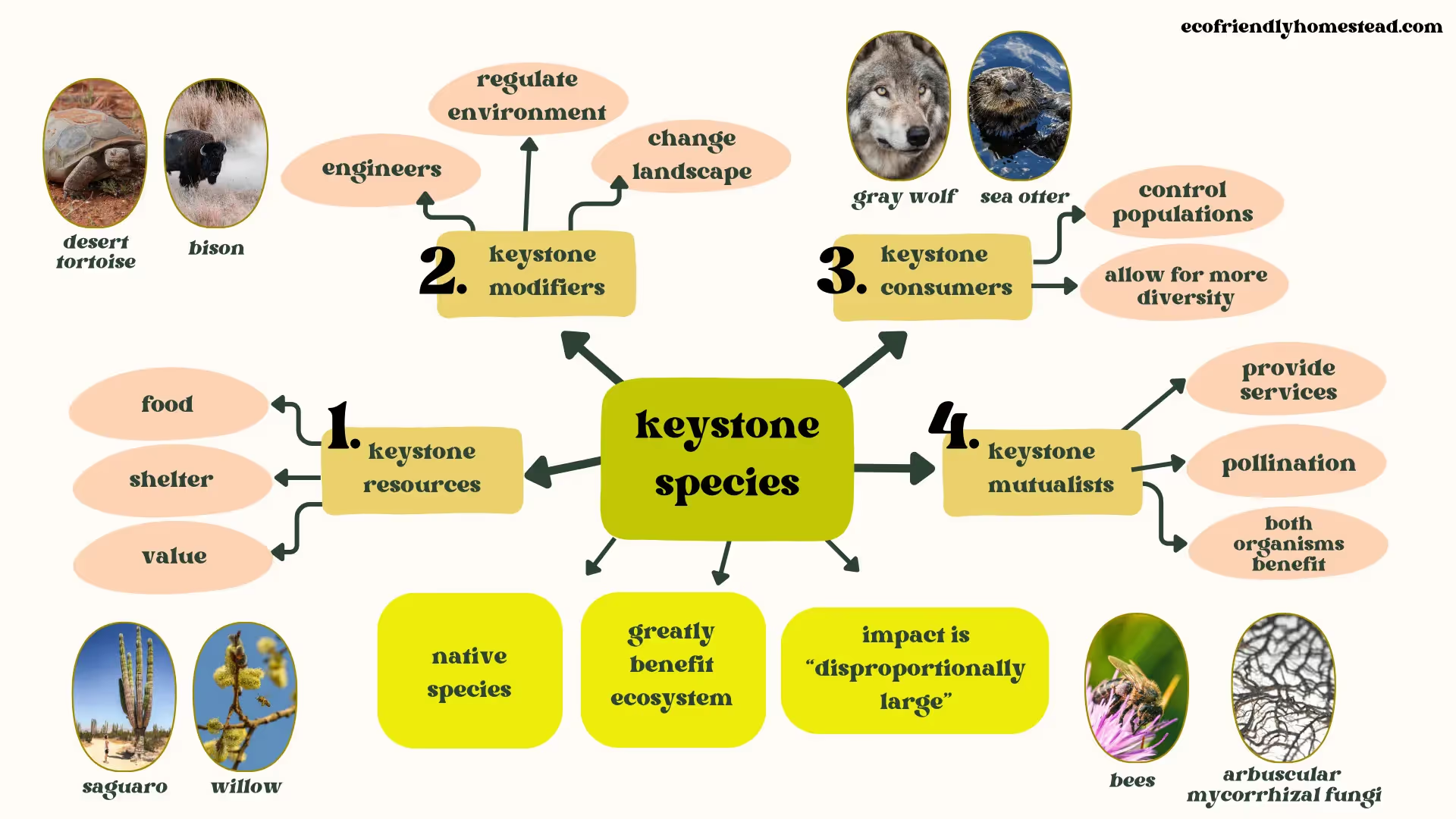

The authors of “Challenges in the Quest for Keystones” share these 4 categories:

Defining Keystone Resources: Nature's Providers:

Keystone resources are species that provide resources to their ecosystem. These resources include food, shelter, pollination, and nesting sites within their habitat.

Willow trees are often considered a keystone resource in varying ecosystems. This is because willow provides one of the first sources of pollen available in early spring.

According to the National Wildlife Federation, various willow trees across the United States are a host plant for 240 caterpillar species. Willow is also a main source of pollen for 19 specialist bee pollinators.

In Sweden, the Goat Willow is a keystone resource plant of special importance. The organization Project PINUS highlights the ways that Goat Willow impacts the surrounding environment:

A saguaro is a type of cactus that is indigenous to the Sonoran Desert of the southwest United States. According to the National Park Service, saguaros are usually 40 feet tall, making it the largest cactus in the States.

The saguaro offers an abundance of resources to the desert ecosystem and is very interconnected with the animals in its habitat.

The National Park Service details how the saguaro offers these resources:

Regenerative gardeners can include keystone plant species within their properties to ensure that these sources of food, shelter, and habitat are available to other animals.

Whenever farmers and gardeners want to follow the regenerative principle of biodiversity, they can plant keystone resource species. This will bring in pollinators, beneficial insects, birds, and other wildlife.

A knowledge of keystone species can also prevent farmers from removing certain trees or plants from the landscape.

For example, I have some willow trees in my yard. I know that these trees are a keystone species, and so I do my best to leave the willow trees in the landscape.

Keystone modifiers create a visible change in the landscape. These changes create certain niche habitats. In turn, the habitat can support a diverse range of species.

Through disturbance or engineering, keystone modifiers regulate their environment. Their impacts create an optimal environment for certain plants and animals to thrive.

Perhaps one of the most commonly recognized keystone engineer species is the beaver.

When beavers build dams, they also:

-Maryland Department of Natural Resources

Another example of a modifier is the bison. This large majestic animal helped to create what we now call the Great Plains. This area of the United States hosts a plethora of plant and animal species. The plains would not be what they are today if it were not from the disturbances caused by the bison.

How did the bison do this? According to the National Wildlife Foundation, the bison carry out these disturbance behaviors to modify the ecosystem:

Bison also are a cultural keystone species. A publication by the Iinnii Buffalo Spirit Center, affiliated with Blackfeet Nation, highlights the interconnectedness of Indigenous peoples and bison.

Harry Barnes, Chairman of Blackfeet Nation, says: “For thousands of years the buffalo has provided food, clothing, and shelter to the Blackfeet people. Our daily lives and our existence was because of this majestic animal.”

The desert tortoise is a beautiful animal that create homes for other animals in their native habitat. Sadly, the desert tortoise is a threatened species.

According to San Diego Zoo, desert tortoises dig burrows to help them regulate their temperature and hide. When the tortoises move on, other desert animals move in. Kangaroo rats, burrowing owls, and gopher snakes all benefit from the pre-made homes of the desert tortoise.

Most farmers who I know hate the sight of soil disturbance caused by voles.

Voles are actually a keystone species that support the ecosystem as a whole…and usually don’t cause much damage to plants. As Oregon State University notes, they prefer to eat grass.

According to Wisconsin Pollinators, voles can distribute mycorrhizal fungi, which are extremely beneficial for plants and carbon sequestration.

Voles create tunnels that aerate the soil, which helps with water infiltration and nutrient delivery to nearby plants.

Soil health and beneficial fungi are two things that regenerative agriculture always looks to increase on crop land.

While voles can cause damage to crops, if we look at creating a robust healthy ecosystem, we can support a balance of their population.

When we encourage wildlife diversity, vole numbers will decrease. This is because voles are also a keystone resource. Voles are a major source of prey within the ecosystem. Snakes, raptors, and other wildlife eat voles. Keystone consumers, such as coyotes, also depend on voles.

Regenerative organic no-till practices provide a healthy environment for voles to exist, while also supporting surrounding wildlife.

Keystone species consumers help to create a population balance within their ecosystem.

Keystone consumers provide equilibrium to an ecosystem. They control populations of animals and plants that would otherwise dominate the environment.

Keystone consumers create space for a greater diversity of animals and plants.

One of the most fascinating stories of Keystone Consumers is the reintroduction of the Gray Wolf to Yellowstone National Park.

According to the National Park Service, the Gray Wolf was reinstated to the Yellowstone area in 1995. The population of wolves grew, and ecologists saw the ways the wolf shifted biodiversity in the park.

Here is how the gray wolf is a keystone species:

(-Outside and National Park Service)

Regenerative gardeners use organic practices that key keystone consumers to thrive. Keystone consumers include beneficial insects that offer pest control in the garden.

Beneficial insects such as wasps, dragonflies, and ground beetles are keystone species that eat common garden pests. The presence of these keystone insects decreases plant damage while increasing yields.

These beneficials thrive in environments that are free from synthetic chemicals and that offer a diversity of plant species - two practices that regenerative gardeners implement.

Keystone mutualists are species that play an essential role in the ecosystem, and get something in exchange for their actions.

The relationship between bees and certain plants is an example of mutualism.

Bees are considered keystone mutualists because they receive pollen and nectar in exchange for pollinating plants and helping plants to reproduce.

A dual benefit paired with essential contributions to an ecosystem is what makes a species a keystone mutualist.

An example of keystone mutualism is the relationship between trilliums and ants. Specifically, the trillium seed distribution by the Aphaenogaster ant.

Trillium is a beautiful woodland flower that blooms in early spring. They thrive in the sunlight they receive before deciduous trees put on their leaves.

The seed of trillium plants are a little bit smaller than a cherry tomato. The seed is surrounded by tasty flesh that the ants love to eat. The part that ants eat is called the elaiosome.

The ants don’t eat the actual seed, so the piles of seeds that they leave behind sprout into new trillium plants.

According to Science, there are 11,000 plants that ants play an active part in distributing. The Aphaenogaster ants in particular can “plant” 70% of seeds in deciduous forests.

What’s more amazing is that ants excrete a disinfecting chemical to clean themselves. This chemical also ends up getting on the seeds. In turn, the seed carries less pathogens that would hinder its germination rate.

Pollinators like bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds support the planet over all. In addition to being mutualistic keystone species, they also provide supporting ecosystem services. Supporting ecosystem services are essential for life on our planet to thrive.

According to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, over 80% of plants that flower need pollination to reproduce.

In exchange for the pollen and nectar that the plant provides, bees make it possible for certain plants to yield food.

CDFW states that over 1200 different crops depend on bees.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are unique organisms that fascinate both gardeners and ecologists alike.

This type of fungi is considered a keystone mutualist for many reasons. According to an article published on Frontiers in Microbiology, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi contribute to their ecosystem in these ways:

AMF do this in exchange for carbohydrates that plants produce in photosynthesis. These carbohydrates fuel the fungi.

Regenerative farmers intentionally work with organic practices to encourage pollinators and mycorrhizal fungi to thrive in their gardens.

No-till farming helps to keep the mycorrhizal fungi population robust, since tilling destroys fungal networks.

Organic inputs and intentional biodiversity support bees and other pollinators in the garden. The mutualistic relationship between bees and crops increases genetic diversity and crop yield.

Now that you know how we can support these critical species, let's consider the broader implications of our efforts towards ecosystem health.

Regenerative organic practices will support the presence of keystone species in your backyard.

When farmers understand the concept of these vital organisms, they can make informed decisions about preserving certain trees or plants.

For example, if you have willow trees in your yard, you know they are vital to the ecosystem and should be preserved.

As a regenerative gardener, you might start to view different animals that you once considered "pests" to now be welcome additions to your garden landscape.

For example, if voles aren't causing too much damage to your yard, you might have a different attitude towards them when you understand their benefits to the ecosystem.

Regenerative gardening works with no-till and organic practices, both of which support the conservation efforts of these essential species in our ecosystem.

I encourage you to notice what keystone species are present around you, and to notice the new perspective that gives you to the roles that both common and rare species play in your local environment.